This article – the third article in our rediscover series, I will take a look at the Soroban Wind Turbine in the small Caribbean Island of Bonaire. Bonaire has an area of 250 square km2 and is located 80 km north of the Venezuelan (more…)

Author: Courtney Powell

-

REdiscover: Munro College Wind Turbine (Jamaica)

In our last rediscover article we looked briefly on the Rosalie Bay Resort Wind Turbine in Dominica. In this article in the article I will look at the Munro College Wind Turbine in Jamaica. (more…)

-

REdiscover: Rosalie Bay Resort Wind Turbine (Dominica)

This post is the first of a series of short articles that I am currently working on. The objective really is to rediscover the small grid connected renewable energy projects commissioned across the Caribbean. (more…)

-

Jamaica’s Policy for the Addition of Renewable Capacity to Electricity Grid

The addition of new generating capacity to Jamaica’s electricity grid can be achieved in three ways:

1. the installation of conventional power plants (more…)

-

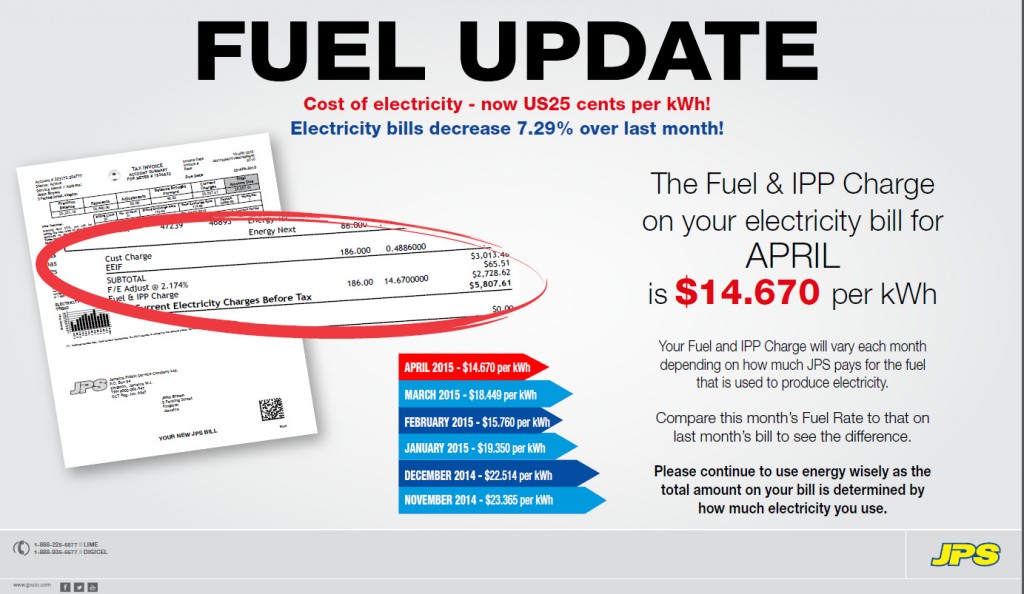

What is the Fuel and IPP charge on your JPS Bill?

The Fuel & IPP Charge on your bill combines two factors: 1) The cost of fuel used to generate electricity and 2) The cost of the electricity supplied by Independent Power Producers (IPPs). The fuel cost is by far the greatest (more…)

-

Average Electricity Cost in Jamaica is Down to Five-Year Low

The average cost of the electricity in Jamaica is currently at a five year low of US 25 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), according to the privately owned electricity company (Jamaica Public Service). JPS says the dramatic (more…)

-

Greening Nevis Electricity Sector

Nevis, the sister isle of St. Kitts, is on its way to becoming carbon neutral in the near future. The two-island state is part of the Leeward Islands chain in the Eastern Caribbean. The small island of Nevis is home to a population of about 12,000 and it receives approximately 90 percent of its energy from imported oil products, with the remaining share coming from wind power. Nevis has its own electric utility, Nevis Electricity Company Limited (Nevlec), which owns and operates capacity of 13.4 MW with peak demand of around 9 MW and a base load of 5 MW.

In 2010, Windwatt Nevis Ltd. (a private developer) installed a 2.2 MW wind park at Maddens Estate. The Maddens Wind Park, which consist of 8 Vergnet 275 kW wind turbines, supplies energy into Nevlec’s 11kV distribution grid. Nevlec is obligated to purchase up to 1.6 MW of energy from the wind park according to the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) between the two companies.

In 2010, Windwatt Nevis Ltd. (a private developer) installed a 2.2 MW wind park at Maddens Estate. The Maddens Wind Park, which consist of 8 Vergnet 275 kW wind turbines, supplies energy into Nevlec’s 11kV distribution grid. Nevlec is obligated to purchase up to 1.6 MW of energy from the wind park according to the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) between the two companies.With wind power experience under its wings, Nevis is now pushing to exploit its vast geothermal energy potential. The Nevis Investment Agency (NIA) is currently welcoming proposals from potential developers with strong financial backing for the development of geothermal. The exploration phase has been completed and it is anticipated that least a 10 MW geothermal plant can be constructed in the not too distant future.

If, or when, this is achieved Nevis will be uniquely placed within the sub-region as a low cost, stable and renewable energy supplier. This project would have many positive benefits for the island including reduction in the cost of electricity; increase employment; energy security; improvement in the investment climate; significant revenue generation from royalty payments, electricity sales domestically including to St. Kitts and potentially neighboring islands. The project would have strong linkages to other sectors such as tourism and agriculture for heating purposes.

If, or when, this is achieved Nevis will be uniquely placed within the sub-region as a low cost, stable and renewable energy supplier. This project would have many positive benefits for the island including reduction in the cost of electricity; increase employment; energy security; improvement in the investment climate; significant revenue generation from royalty payments, electricity sales domestically including to St. Kitts and potentially neighboring islands. The project would have strong linkages to other sectors such as tourism and agriculture for heating purposes. -

Harnessing Geothermal Energy for Electricity Generation

In a previous article titled “Geothermal Potential in the Caribbean,” I highlighted the vast geothermal energy potential of several of the islands.

The history of electricity production from geothermal energy dates back to the early 1900s. However, of the islands in the Caribbean with geothermal potential, to date, only Guadeloupe has a 4.5MWe geothermal electricity plant.

A conventional geothermal power plant taps into the earth’s hydrothermal circulation system via a production well to capture hot water or steam which is then used to drive steam turbines. The turbines intern drive electric generators to produce electricity, as shown in figure 1. The captured geothermal fluids are then returned to the earth via an injection well also shown in figures 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 1: Geothermal Power Plant (source:www.energy.gov) There are primarily three types of geothermal power plants namely Dry Steam, Flash Steam and Binary Cycle. All operate on the principle of pulling hot water and steam from the ground, using it, and then returning it to prolong the life of the heat source. A dry steam plant operates on hydrothermal fluid that is primarily steam, the steam is passed directly into the turbine to produce electricity. The steam then condenses (turns to water) and returns to the earth, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Dry Steam Geothermal Power Plant (source: http://www.energy.gov) A flash steam plant, on the other hand, uses hydrothermal fluids above 360°F (182°C). The fluid is sprayed into a flash tank, which is at a much lower pressure than the fluid, causing some of the fluid to rapidly vaporize, or “flash. The vapour or steam then drives the turbine, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Flash Steam Geothermal Power Plant (source: http://www.energy.gov) A binary cycle plant, unlike the dry steam and flash steam plants, uses a heat exchange system and a secondary fluid – such as isobutene – to capture the energy from the hydrothermal fluid of moderate temperature (below 400°F). This secondary fluid, which is used to drive the turbine as shown in figure 4, has a much lower boiling point causing it more easily convert into vapour.

Figure 4: Binary Cycle Geothermal Power Plan (source: http://www.energy.gov) The design choice is driven mainly by the nature of the available resources, however since moderate-temperature water is by far the most common geothermal resource, then future geothermal projects will mostly be binary cycle geothermal power plants. The 4.5MWe plant in Guadeloupe is a binary cycle power plant.

-

The Economics of Wind Power in Jamaica

In late 2013, the Office of Utilities Regulation (OUR) named three preferred bidders for the supply of up to 115 MW (megawatts) of electricity generation capacity from renewable energy. The three preferred bids amounted to a total 78 MW of energy only renewable energy capacity, including two projects offering energy from wind amounting to 58 MW, and one offering solar amounting to 20 MW. The proposed delivery price to the grid ranged from US$0.1290 to US$0.1880.

The preferred bidders were:

1. Blue Mountain Renewables LLC, to supply 34 MW of capacity from wind power at Munro, St. Elizabeth;

2. Wigton Windfarm Limited, to supply 24 MW of capacity from wind power at Rose Hill, Manchester; and

3. WRB Enterprises Inc., to supply 20 MW of capacity from Solar PV from facilities in Content Village, Clarendon.

The 20 MW solar farm will be the first of its kind in the Island, however Jamaica’s first grid-connected wind-powered generator was commissioned in February 1996 at Munro College. This wind turbine-generator, a Vestas V27 – 225 kW, was also the first grid-connected wind-energy source in the English-speaking Caribbean. The project was funded primarily by the Environmental Foundation of Jamaica (EFJ), but also included a long list of local companies and individuals. The total installation cost of the facility was US$300,000. However, much of the local services, such as JPSCo’s services and Alpart’s crane services, were donated free of cost.

The overwhelming success of the the Munro College wind turbine encouraged the Petroleum Corporation and the Government of Jamaica to commission Jamaica’s first large scale wind farm at Wigton (in the parish of Manchester) in 2004. The initial 20.7 MW wind farm, which came to be known as Wigton I, comprises of twenty three (23) NEG Micon NM52 – 900 kW wind turbines. The project was financed at a total cost of US$26.2 million with equity injection of US$ 3.2 million from the Petroleum Corporation of Jamaica (PCJ), a US$ 16 million loan from the National Commercial Bank of Jamaica (NCB) and a grant of US$ 7.0 million from the Netherlands Government.

A midst several changes, including $150 million in lost revenues due to unfavorable energy rates and $120 million due to penalties imposed by JPS for reactive power demand and a fail divestment attempt in early 2007, the Wigton wind farm was expanded during the period 2009 to 2010 to include nine (9) Vestas V80 -2.0 MW wind turbines. The 18 MW project, now called Wigton II, was financed from the PetroCaribe Development Fund at total cost of US$49.9 million.

In late 2010, JPS (the owner and operator) commissioned its first wind project – a 3 MW wind farm at Munro, St. Elizabeth. This project comprises of four (4) UNISON U50 – 750 kW wind turbines and was completed at a total cost of US$9.3 million. The Munro wind farm interconnects to JPS 24kV distribution system unlike the Wigton wind farms, which interconnects to JPS 69kV system via a 11km long tie-line. It is worthwhile noting that the grid interconnection cost can account for as much as 8-9% of the total project cost. In the case of the Wigton wind farms the 11kM 69kV line was included in the capital cost of the initial project.

The two new wind farms coming out of the OUR latest request for renewable energy in addition to the national grid are projected to cost US$40 million for the WWF’s (Wigton Windfarm) 24 MW wind farm and US$90 million for the BMR’s (Blue Mountain Renewables) 34 MW wind farm. The cost of these two project forces me to ask one key question “how does public vs private investor wind power projects costs compare?”. I thought that a good way to get a fair comparison was to look at the projects that had/have the same/similar time horizon. So, I decided to firstly compare the Wigton II and JPS Munro wind farm projects (which were both commissioned in 2010) and secondly the proposed Wigton III and BMR Munro wind farm projects (both scheduled to be commission in 2016), as shown below.

This comparison revealed two important facts:

1. Private investor wind projects in Jamaica cost more than public wind projects. In the first case, the JPS Munro wind farm cost approximately 1.1 times the cost of the Wigton II wind farm on a per megawatt basis. Similarly, the proposed BMR Munro wind farm will cost approximately 1.6 times the proposed Wigton III wind farm on a per megawatt basis. It would be good to see a breakdown of the project cost to see exactly where the projects varied in term of cost.

2. The cost of wind power has come down by 40% for public projects and 15% for private projects since 2009.

The cost of a wind project has a lot to do with its total size (economics of scale) however the most common way to compare wind project cost is on a per megawatt basis, as was done here. It is also worthwhile to add that the basic cost components of wind projects typically include: turbine cost, grid interconnection, foundation, electrical installation, consultancy, financial cost, road construction, control systems, etc. The inserted table gives a break down of the % share of the total cost for each component.

The cost of a wind project has a lot to do with its total size (economics of scale) however the most common way to compare wind project cost is on a per megawatt basis, as was done here. It is also worthwhile to add that the basic cost components of wind projects typically include: turbine cost, grid interconnection, foundation, electrical installation, consultancy, financial cost, road construction, control systems, etc. The inserted table gives a break down of the % share of the total cost for each component.Public projects, in most cases, could have a competitive advantage in terms of the land rental, financial cost and road construction components which could possibly explain to some extent why public projects have been carrying lower project cost compared to the few private projects that we have seen in Jamaica’s recent renewable energy history.

-

JPS proposes massive residential rate increase!

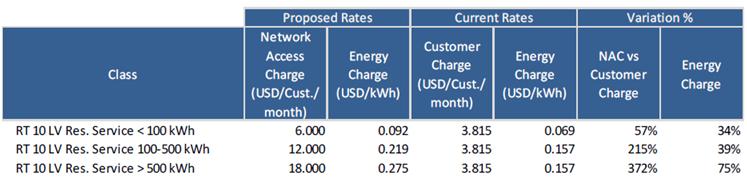

As some of you may already know, JPS has made an application to the OUR for an increase in its non-fuel tariff rates. This was done in accordance with their exclusive all-island electricity licence, which stipulates that JPS must submit a filing with the OUR to obtain new rates at the end of every five year period. The licence also allows for a monthly adjustment due to foreign exchange changes and an annual adjustment to cater for inflation.

Data obtain from the MSTEM showed that over the last period 2009 to 2013, JPS has increased its rates on average by 15% annually for each class of customer, as shown in the chart above. In its recent submission for the period 2014-19, while acknowledging that Jamaica and by extension its customers are experiencing an economic contraction, JPS proposes a massive 21% increase in the average residential customers electricity bill. The average commercial customer will also see an increase of 15%, while the average industrial customer will see a small 1.5% reduction.

Be that as it may, the proposed 21% hike in residential electricity bill has definitely sparked my interest. It did so to the point that I decided to take a quick glance through their application document (feel free to take a look). As a result, I decided to present some of the information that I think will give you’ll a heads up on what your bill might look like if the OUR approves the proposal as is (and for simplicity I focused only on the residential class, since that affects all of us).

The following table shows the proposed rates in addition to the current ones in US dollars ($1 US = $112 JM). Note that the residential customer class is divided into three tiers, as shown in the left column.

A a network access charge is now being proposed to replace the customer charge. This change brings with it a hefty increase, up to 372%. Is this ridiculous or not?

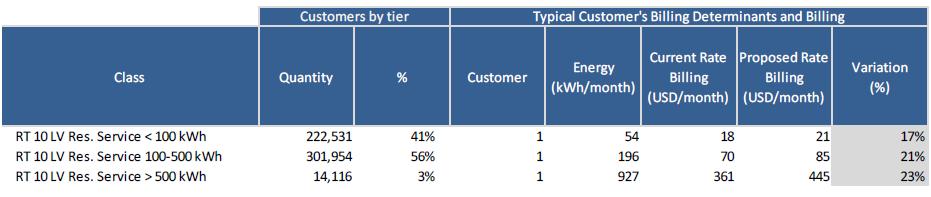

The next table shows the percentage increase to be expected on average per tier. It also showed that the average consumption per tier is 54, 196 and 927 kWh (this is the unit used to measure you electricity usage) and the monthly expected increase is 17, 21 and 23% respectively. So that’s where the 21% stated above and in the print media came from.

To put this into prospective, say for example that you are the average customer in the second tier (100-500kWh) with monthly energy consumption of 196kWh, you current bill would be $7,891.00 per month. However, after the increase you new bill would be $9,567.00 per month. This plus the bill impact of the other tiers are shown in the following table:

The document is a detailed and lengthy one and though I did not get the time to digest the content in its entirety, I can’t help but feeling that JPS is shifting too much of the burden unto the residential and small commercial customers while at the same time lowering the cost to large commercial and industrial customers. This they say is in a bid to “provide an attractive tariff to the largest industrial customers to encourage economic growth and development for the country.”

However, my gut feeling is telling me that this a trap engendered to keep customers connected to the grid. How? Firstly, the lowering of the tariff for large commercial and industrial customers will be a disincentive to the utilization of the wheeling/net-billing policies, since this will affect the economics gains of these options. And secondly, smaller customers are less likely to afford to go off the grid or put another way the economic gains are negligible.

What are your thought? Feel free to comment below or inbox me via the about page.

Thanks for reading!

CP.