Wind as a source of electric energy in the Caribbean is now becoming commonplace, with utility-scale wind power plants in operation on Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Jamaica, Nevis, Puerto Rico, and Martinique. Barbados, Guyana, and St. Lucia are next in line to add utility-scale wind energy to their energy mix.

Utility-scale wind power plants consist of several wind turbines, most of which are usually connected to each other in a daisy-chained fashion. The turbine, which is the heart of the plant, converts the kinetic energy of wind into electricity. A modern wind turbine consists of a three-blade rotor that captures the energy from the wind and drives a generator to produce electricity. The rotor and the nacelle, which contained the electric generator and the other necessary parts, are installed at the top of a tower, as shown below. The nacelle and the blades are controlled based on measurements of the wind speed and direction.

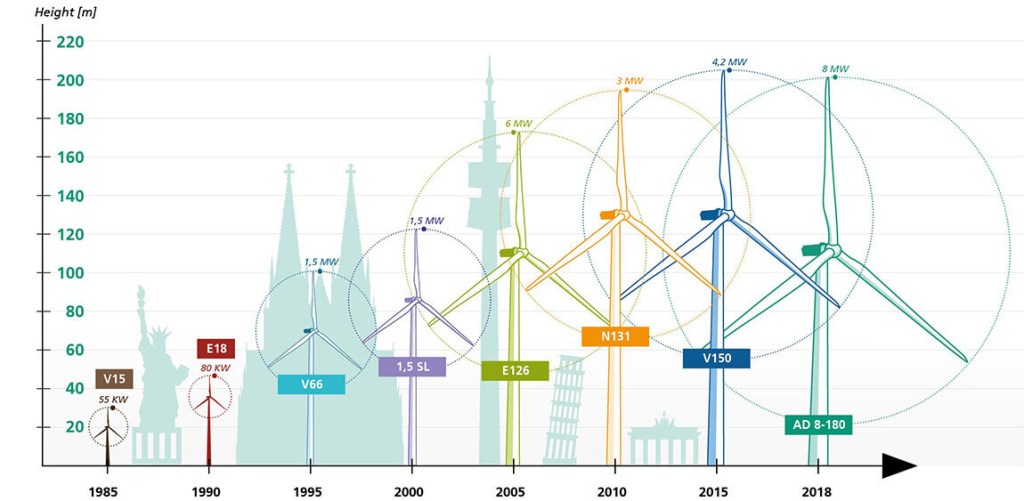

The amount of power that a wind turbine can extract from the wind is primarily dependent on the rotor swept area (A) and the wind speed (U). Therefore, to extract maximum energy from the wind, turbine manufacturers have been increasing the rotor diameter of their wind turbines over the decades, as shown below. Likewise, wind farm developers are always scouting for areas across the globe with high and stable wind speed all year round to develop economically competitive wind projects.

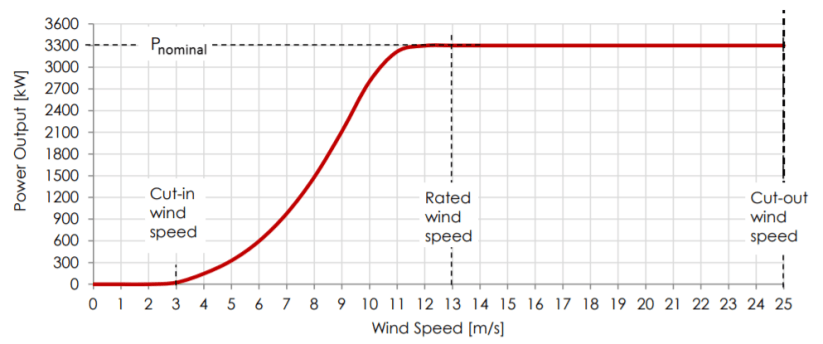

The actual power output of a wind turbine is limited by physical restrictions and is best illustrated by its power curve. The power curve of a wind turbine shows the electrical power output of the wind turbine versus the wind speed. An example of a power curve is shown below. It represents a Vestas V112-3.3 wind turbine as used in the case of the BMR wind farm in Jamaica. It has a rotor diameter of 112 meters and a rated/nominal power of 3.3 MW.

The operating range of the wind turbine is defined by the cut-in and cut-out wind speeds. At the cut-in wind speed, typically around 3 m/s, the turbine starts to operate and produce electric energy. The cut-out wind speed, 25 m/s in the case of the V112-3.3 turbine, demarcates the upper safe operating wind speed at which point the turbine will stop producing electric energy and shut itself down. The rated wind speed is the wind speed at which the turbine produces its rated power output. The rated power of the V112-3.3 turbine is reached at 13 m/s.

If this wind turbine was to operate at rated power for one hour it would produce 3.3 MWh (3,300 kWh). This is approximately 150% of the annual energy consumption of the average family home in Jamaica. However, wind turbines don’t always operate at their rated power output, due to the variability of the wind speed. Therefore, a measure known as capacity factor, is typically used to assess the efficiency of a turbine or wind farm. It is defined as the average power output of a wind turbine/farm as a percentage of the rated power of the turbine/wind farm.

For most wind turbines erected on land, the capacity factor is between 20-40% or expressed in full-load hours it is around 1,800-3,500 hours per annum. The capacity factor for the Wigton and BMR wind farms in Jamaica are shown in the following table along with their rated power and estimated annual energy production based on their capacity factors.

| Wind Farm | Capacity (MW) | Capacity Factor (%) | Annual Energy (MWh) |

| Wigton I | 20.7 | 35 | 63,466.20 |

| Wigton II | 18 | 33 | 52,034.40 |

| Wigton III | 24 | 30 | 63,072.00 |

| BMR | 36.3 | 34 | 108,115.92 |

| Munro | 3 | 40 | 10,512.00 |

| Total | 102 | 32 | 286,688.52 |

From the total install capacity of 102 MW and the total estimated annual energy of 286,688,52 MWh, an overall capacity factor of 32% is estimated.

In part 2, we will look at turbine design parameters for specific wind sites.